by Matthew E. Borrasso I October 21, 2020

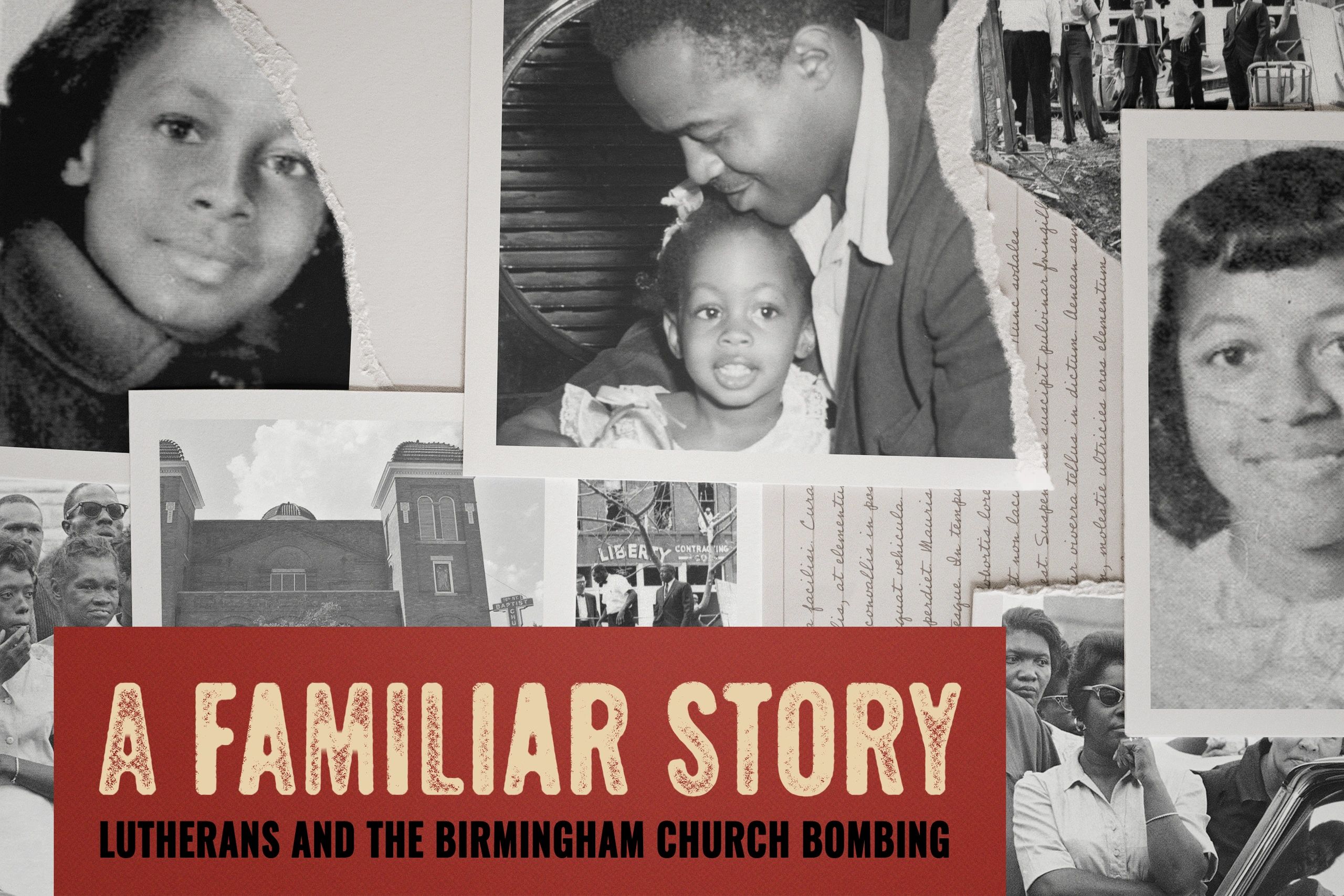

ON SEPTEMBER 15, 1963 AT 10:22AM, sticks of dynamite white supremacists had tucked under the basement stairs of Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, ripped a hole in the building and the hearts of many. Four girls, Adie Mae Collins, Carole Robertson, Cynthia Wesley, and Denise McNair, were killed. Like most Americans, I’ve been generally aware of this vicious and tragic event for most my life. But if I’m honest, the bombing occurred twenty-two years before I was born, in a state I’ve only driven through, in a town I’ve never set foot in, during an era I’ve never experienced, to people I’ve never met. It’s not a story I have ever considered to be my own or one I could be close to or call familiar. History, however, has a way of broadening one’s perspective.

While researching the events surrounding the Birmingham Church bombing, I made a startling discovery: two of the young victims had connections to my own church body, The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod. Fourteen-year-old Cynthia Wesley frequented Prince of Peace Lutheran Mission in Birmingham. Eleven-year-old Denise McNair and her mother were members at Sixteenth Street but her father was a member at St. Paul’s Lutheran Church. In all my years as a Missouri Synod elementary school student, member, and now pastor, I don’t remember having ever heard this part of the story. And the story doesn’t end with the bombing.

Following the events of that tragic day, Rev. Joseph Ellwanger of St. Paul’s Lutheran participated in Denise McNair’s memorial service at her parents’ request, but against the advice of his District President. The concern of his District President arose because Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was slated to preach the homily (Missouri Synod pastors commit themselves to participating in worship services with only other Missouri Synod clergy). Ellwanger, who is no longer part of the Missouri Synod, ignored his District President. “I am as the pastor of the father of one of these girls. He asked me—he and his wife asked me—to lead their family in prayer before the funeral and to participate in the funeral, and I am going as a witness to the Gospel; I will be there.” [1]

Ellwanger made good on his word and then some: The day after the bombing, he and eight other LCMS pastors came together in Birmingham and composed a statement. It reads as follows:

The Christian church should never dodge an issue that involves the life, practice, and the Christian confession of its people. Our community has been stunned by the loss of life through the bombing of a church in Birmingham, Alabama on Sunday, Sept. 15th, 1963.

This act of violence is the responsibility of a man or a group of men. The guilt of such violence is ours also because we did not heed the Savior’s directive that “we love one another.” To the extent that we have supported forced segregation by our words or silence, we have given encouragement to such lawlessness. We must repent.

We as Lutheran Christians are compelled by the Word of God to believe that the church is not a segregated community. We are one in Christ. The members of our congregations as part of the body of Christ therefore have no right to segregate any member of that body.

The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod has reiterated its stand on this issue in a resolution of June 1959, which reads: “It is wrong for the Christian to try and justify any kind of racial discrimination.”

“We acknowledge our responsibility as a church to provide guidance to our members to work in the capacity of Christian citizens for the elimination of discrimination wherever it may exist in community, city, state, nation, and world.” [2]

Even though the statement was controversial for some, the Council of Presidents of the LCMS (the President, Vice-Presidents, and District Presidents) drafted a resolution to support it and its authors. The boldness of both the statement and Council’s support was striking to me -- all the more so when I learned that, within the LCMS, there was a fair amount of opposition to engaging in the struggle to end segregation. The Lutheran Witness ran an editorial about the bombing that helps shed light on the resistance.

There are those who protest the entry of churches into the racial question. “Lay it off,” they say. “This is a social issue. The churches should stick to preaching the Word of God.” Also: “Why is segregation a sin today if it was not morally wrong 100 years ago? Part of the answer to both objections would be that only belatedly have some churches come to grasp the Gospel of Christ has social implications…. Churches will not shape the thinking of Christians and exert an influence on society unless they identify themselves with moral issues of the day. Because segregation is high on the list, Christians must speak and act on the racial issue. [3]

Even as I reread that editorial, it strikes me as something that is strange and yet familiar. Lutherans today do believe that “Christians must speak and act” on “moral issues” but those issues are typically limited to issues of life, marriage, and religious freedom. And yet, at one point, those “moral issues” that “Christians must speak and act on” were intimately connected to racial identity and a caste system of subjugation. At one point, pastors came together to decry the evils of violence against four little girls who were slaughtered simply because they were Black. If nothing else, this historical moment can remind us that empathy led to action.

For me, the most moving part of the pastors’ statement is the confession embedded within the second paragraph. While they recognize that “this act of violence is the responsibility of a man or a group of men,” they also confess that, “the guilt of such violence is ours also because we did not heed the Savior’s directive that ‘we love one another.’” Moreover, they recognize the need for repentance. “To the extent that we have supported forced segregation by our words or silence, we have given encouragement to such lawlessness. We must repent.” These pastors didn’t bomb the church. These pastors were not personally racist. These pastors did realize, however, that sometimes people can reinforce problematic attitudes and perspectives unintentionally—sometimes silence is precisely what Dr. King called it, betrayal.

I once had a professor say that her job as a historian was to “make the strange feel familiar and the familiar feel strange.” Her perspective on historical inquiry broadened my own. The thing is, though, that the broadening of perspective is only valuable insofar as it shapes who I am. Historical inquiry at its best leads toward introspection and action—it helps me understand myself and my neighbor and hopefully helps me love them both a little more. It gives me an opportunity to repent in order that I might try, and likely fail, to do better—not better than others, but better than my own yesterday. It challenges me not only to avoid the mistakes of the past but also calls me to consider how I engage with the world around me and the neighbor beside me. In reality, it shouldn’t have taken a Lutheran connection for me to make the story of the bombing in Birmingham my own. Such a thing betrays the fact that I am too insulated by my own cultural moment to see how connected I am to people who lived, and died, in an era distant from my own.

Thank God that the path to healing doesn’t start with me, but with the very same Word that compelled those pastors to issue a statement in the wake of a tragedy. It starts with the Word that compels me to repentance for not heeding my Savior’s directive to love my neighbor as myself. It starts with the Word that compels me to acknowledge my responsibility as part of the church “to work in my capacity as [a] Christian [citizen] for the elimination of discrimination wherever it may exist in community, city, state, nation, and world.” It starts with the Word that compels me to fall over and over again at the foot of the cross, receiving there the absolution that only Christ can give. It starts with the Word that compels me to hear my Lord and serve my neighbor, no matter how familiar their story.

Matthew E. Borrasso is a pastor at Redeemer Evangelical Lutheran Church in Parkton, MD. More writing from Matt: https://mattborrasso.com/.

[1] Rev. Ellwanger is quoted as saying this to Richard O. Ziehr in a phone interview on March 21, 1996. See Richard O. Ziehr, The Struggle for Unity: A Personal Look at the Integration of Lutheran Churches in the South (Milton, FL: CJH Enterprises, 1999), 135.

[2] The Lutheran Witness, October 15, 1963, 19. Quoted in Richard O. Ziehr, The Struggle for Unity: A Personal Look at the Integration of Lutheran Churches in the South (Milton, FL: CJH Enterprises, 1999), 133.

[3] The Lutheran Witness, October 1, 1963, 3, 4. Quoted in Richard O. Ziehr, The Struggle for Unity: A Personal Look at the Integration of Lutheran Churches in the South (Milton, FL: CJH Enterprises, 1999), 133–134.